“This Legality, therefore, is not able to set thee free from thy burden. No man was as yet ever rid of his burden by him; no, nor ever is like to be: ye cannot be justified by the works of the law; for by the deeds of the law no man living can be rid of his burden: therefore, Mr. Worldly-wiseman is an alien, and Mr. Legality is a cheat; and for his son Civility, notwithstanding his simpering looks, he is but a hypocrite, and cannot help thee. Believe me, there is nothing in all this noise, that thou hast heard of these sottish men, but a design to beguile thee of thy salvation, by turning thee from the way in which I had set thee.”

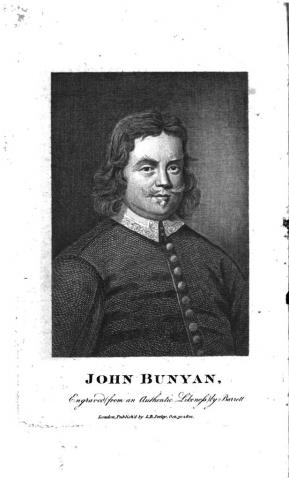

John Bunyan, The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678), Desiring God, Minneapolis, 2014, p. 23

La loi est donc incapable de te libérer de ton fardeau. Aucun homme n’a jamais été justifié par les œuvres de la Loi*. C’est pourquoi Mondain est un trompeur, ainsi que son ami la Loi. Son fils Courtoisie n’est qu’un hypocrite, malgré son air honnête, et il ne peut pas t’aider. Crois moi, cet homme stupide n’a pas eu d’autre but que de te détourner de ton salut, et de te faire sortir du chemin dans lequel je t’avais introduit.

John Bunyan, Le voyage du pèlerin (1678), CLC France, Montélimar, 2015, p. 38

* Romans 3:20 : “Therefore no one will be declared righteous in God’s sight by the works of the law; rather, through the law we become conscious of our sin.”

Romains 3:20 : “Car nul ne sera justifié devant lui par les œuvres de la loi, puisque c’est par la loi que vient la connaissance du péché.”