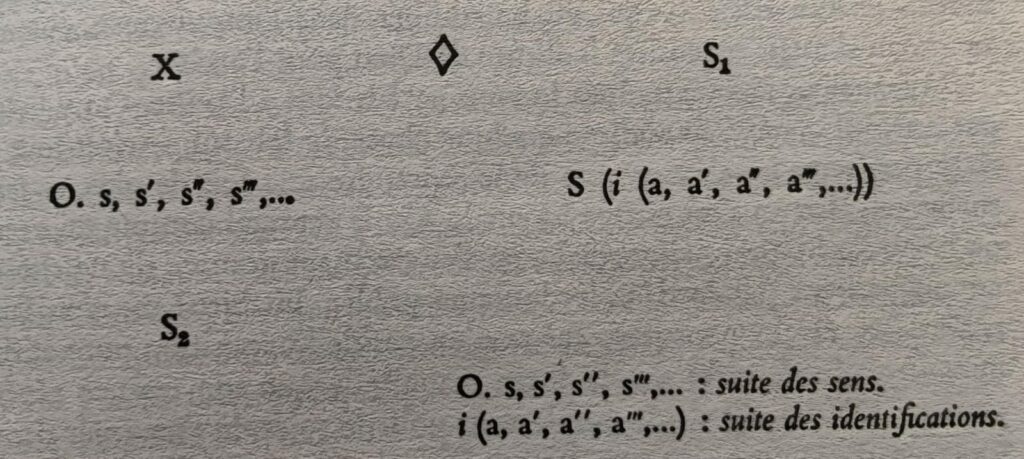

I will go so far as to formulate that, when there is no interval between S1 and S2, when the first dyad of signiflers become solidified, holophrased, we have the model for a whole series of cases — even though, in each case, the subject does not occupy the same place. In as much, for example, as the child, the mentally-deficient child, takes the place, on the blackboard, at the bottom right, of this S, with regard to this something to which the mother reduces him, in being no more than the support of her desire in an obscure term, which is introduced into the education of the mentally-deficient child by the psychotic dimension. It is precisely what our colleague Maud Mannoni, in a book that has just come out and which I would recommend you to read, tries to indicate to those who, in one way or another, may be entrusted with the task of releasing its hold. It is certainly something of the same order that is involved in psychosis. This solidity, this mass seizure of the primitive signifying chain, is what forbids the dialectical opening that is manifested in the phenomenon of belief. At the basis of paranoia itself, which nevertheless seems to us to be animated by belief, there reigns the phenomenon of the Unglauben. This is not the not believing in it, but the absence of one of the terms of belief, of the term in which is designated the division of the subject. If, indeed, there is no belief that is full and entire, it is because there is no belief at does not presuppose in its basis that the ultimate dimension that it has to reveal is strictly correlative with the moment when its meaning is about to fade away.

Jaques Lacan, The four fundamental concepts of psychoanalysis, The Seminar Book Xl, Tr. Alan Sheridan, Norton & company, London New York, 1998, P. 237

J’irai jusqu’à formuler que, lorsqu’il n’y a pas d’intervalle entre S, et S₂, lorsque le premier couple de signifiants se solidifie, s’holophrase, nous avons le modèle de toute une série de cas – encore que, dans chacun, le sujet n’y occupe pas la même place.

C’est pour autant que, par exemple, l’enfant, l’enfant débile, prend la place, au tableau, en bas et à droite, de ce S, au regard de ce quelque chose à quoi la mère le réduit à n’être plus que le support de son désir dans un terme obscur, que s’introduit dans l’éducation du débile la dimension psychotique. C’est précisément que notre collègue Maud Mannoni, dans un livre qui vient de sortir et dont je vous recommande la lecture, essaie de désigner à ceux qui, d’une façon quelconque, peuvent être commis à en lever l’hypothèque.

C’est assurément quelque chose du même ordre dont il s’agit dans la psychose. Cette solidité, cette prise en masse de la chaîne signifiante primitive, est ce qui interdit l’ouverture dialectique qui se manifeste dans le phénomène de la croyance.

Au fond de la paranoïa elle-même, qui nous paraît pourtant tout animée de croyance règne ce phénomène de l’Unglauben. Ce n’est pas le n’y pas croire, mais l’absence d’un des termes de la croyance, du terme où se désigne la division du sujet. S’il n’est pas de croyance qui ne suppose dans son fond que la dimension dernière qu’elle a à révéler est strictement corrélative du moment où son sens va s’évanouir.

Jacques Lacan, Les quatre concepts fondamentaux de la psychanalyse, le Séminaire livre XI (1963-1964), Editions du Seuil, Paris, 1973, p. 215