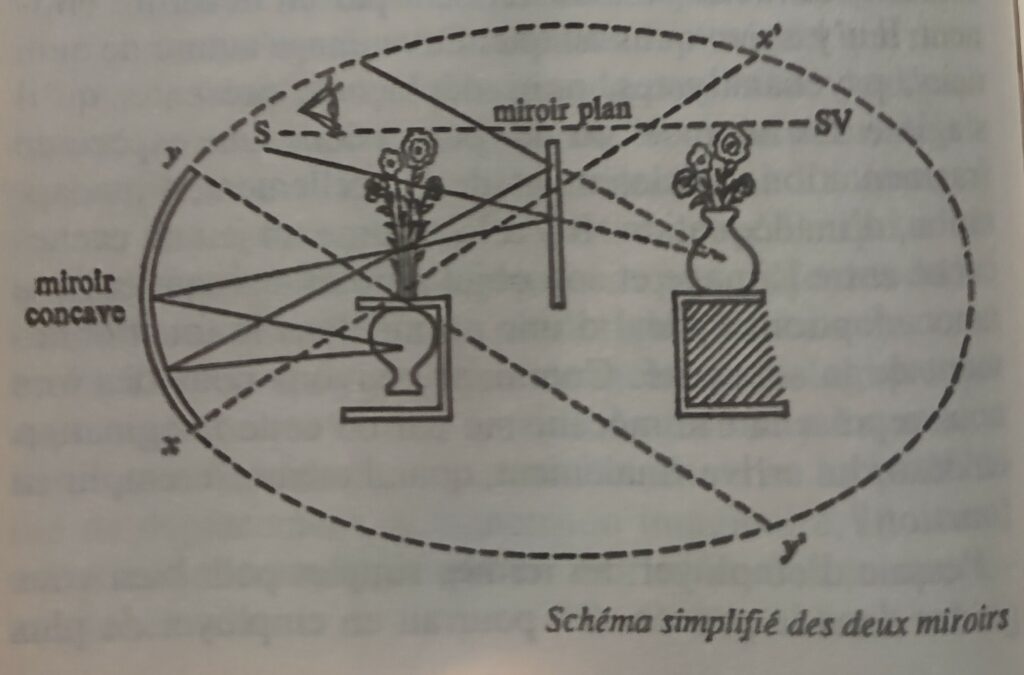

Now let us postulate that the inclination of the plane mirror is governed by the voice of the other. This doesn’t happen at the level of the mirror-stage, but it happens subsequently through our overall relation with others – the symbolic relation. From that point on, you can grasp the extent to which the regulation of the imaginary depends on something which is located in a transcendent fashion, as M. Hyppolite would put it – the transcendent on this occasion being nothing other than the symbolic connection between human beings. What is the symbolic connection? Dotting our i’s and crossing our t’s, it is the fact that socially we define ourselves with the law as go-between. It is through the exchange of symbols that we locate our different selves [mois] in relation to one another – you, you are Mannoni, and me Jacques Lacan, and we have a certain symbolic relation, which is complex, according to the different planes on which we are placed, according to whether we’re together in the police station, or together in this hall, or together travelling.

Jacques Lacan, The Seminar of Jacques Lacan – Book I – Freud’s paper on Technique (1953-1954), Trans. John Forrester, Norton Paperback, New-York, 1991, p. 140 – 141

In other words, it’s the symbolic relation which defines the position of the subject as seeing. It is speech, the symbolic relation, which determines the greater or lesser degree of perfection, of completeness, of approximation, of the imaginary. This representation allows us to draw the distinction between the Idealich* and the Ichideal*, between the ideal ego and the ego-ideal. The ego-ideal governs the interplay of relations on which all relations with others depend. And on this relation to others depends the more or less satisfying character of the imaginary structuration.

Nous pouvons supposer maintenant que l’inclinaison du miroir plan est commandée par la voix de l’autre. Cela n’existe pas au niveau du stade du miroir, mais c’est ensuite réalisé par notre relation avec autrui dans son ensemble – la relation symbolique. Vous pouvez saisir dès lors que la régulation de l’imaginaire dépend de quelque chose qui est situé de façon transcendante, comme dirait M. Hyppolite – le transcendant dans l’occasion n’étant ici rien d’autre que la liaison symbolique entre les êtres humains.

Jacques Lacan, Le Séminaire – Livre I – Les écrits techniques de Freud (1953-1954), Le Seuil, 1998, p. 222 – 223

Qu’est-ce que c’est que la liaison symbolique ? C’est, pour mettre les points sur les i, que socialement, nous nous définissons par l’intermédiaire de la loi. C’est de l’échange des symboles que nous situons les uns par rapport aux autres nos différents moi – vous êtes, vous, Mannoni, et moi, Jacques Lacan, et nous sommes dans un certain rapport symbolique, qui est complexe, selon les différents plans où nous nous plaçons, selon que nous sommes ensemble chez le commissaire de police, ensemble dans cette salle, ensemble en voyage.

En d’autres termes, c’est la relation symbolique qui définit la position du sujet comme voyant. C’est la parole, la fonction symbolique qui définit le plus ou moins grand degré de perfection, de complétude, d’approximation, de l’imaginaire. La distinction est faite dans cette représentation entre l’Ideal-Ich* et l’Ich-Ideal*, entre moi-idéal et idéal du moi. L’idéal du moi commande le jeu de relations d’où dépend toute la relation à autrui. Et de cette relation à autrui dépend le caractère plus ou moins satisfaisant de la structuration imaginaire.

Jacques Lacan, Le Séminaire – Livre I – Les écrits techniques de Freud (1953-1954), Le Seuil, 1998, p. 222 – 223

* Ideal-ego and Ego-ideal in german in the text